menu

Implementation

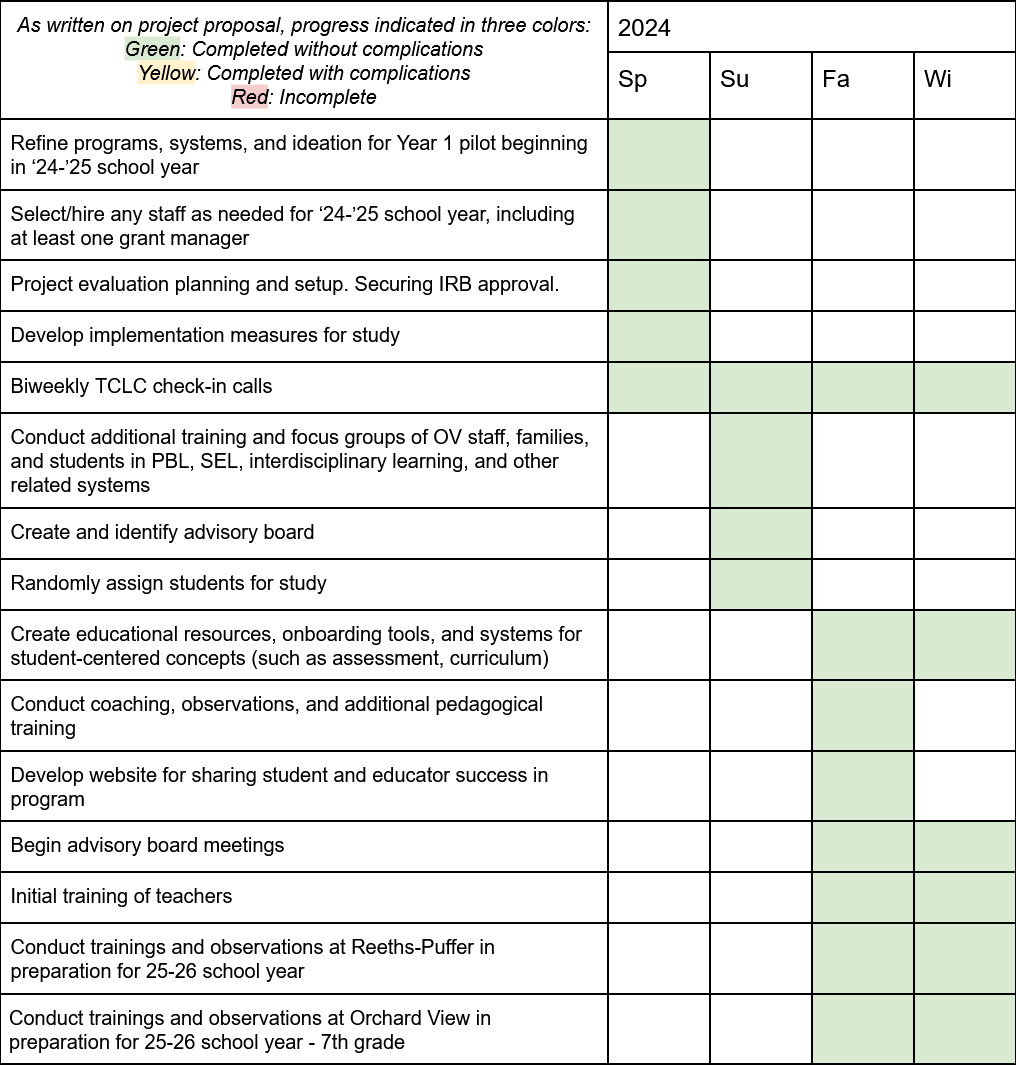

TCLC set out to change major systems and practices in high-needs public middle schools and our initial first year has been a resounding success. Below, we will communicate milestones and their progress from our project narrative’s projected timeline:

Table A: Project Timeline (Evaluation Timeline detailed in Table B)

Refine programs, systems, and ideation for Year 1 pilot beginning in ‘24-’25 school year

In close partnership with Orchard View Schools (OV), Human Restoration Project (HRP) and Open Way Learning (OWL) worked with inner-district tools (e.g. PowerSchool) to develop “front of house” and “back of house” schedules to implement 10 hours of interdisciplinary project-based learning (iPBL) per week in OV’s 6th grade TCLC cohort. The minimum required by our proposal was 3 hours.

Teachers became highly interested in the program through close partnerships in previous years as well as some experience in project-based learning. As a result, they wanted to commit additional time to this model, replacing their typical social studies and science classrooms with iPBL – meeting the standards of these classes within the overarching project period – and having an additional mathematics and English class for district-mandated curriculum. That said, all teachers taught all subjects within the iPBL period.

In addition, HRP worked with OV to lessen the number of district required grades per year (down to 1 per quarter) to ensure that students had the necessary time to build portfolios and iterate on their designs as necessitated by portfolio-based, feedback-driven assessment (PBFDA).

Select/hire any staff as needed for ‘24-’25 school year, including at least one grant manager

HRP recruited Cassie Nastase as the Third Coast Learning Collaborative grant manager. Ms. Nastase previously served as a guidance counselor at booth OV and Reeths-Puffer (RP) schools with close connections to the teachers and students on this project; as well as serving as a community leader with close connections to businesses and organizations. This has proven invaluable for our project, as she has not only been able to track and communicate ongoing progress in Muskegon, MI, but served as a project connector/ambassador for student learning into the local community.

All teachers in OV 6th grade were previously identified as wanting to join the TCLC cohort when applying for the EIR grant, and continued to join the cohort for the 2024-2025 school year.

Project evaluation planning and setup. Securing IRB approval.

The University of Virginia (UVA) was able to secure IRB approval for human subjects before starting our study in the school year; and worked with the TA staff to develop a holistic model of measuring student learning, success, and challenges (see Summary Area II).

Biweekly TCLC check-in calls

Starting in March 2024, HRP has held consistent bi-weekly (twice per month) meetings with leaders from OWL, OV, RP, the Muskegon ISD, and UVA. These meetings were consistently attended by administrators to talk about needs to implement TCLC (e.g. support for board meetings, scheduling processes, school event disruptions) as well as ensuring grant requirements were being met (e.g. matching funds hours logging, reporting data).

These meetings have been instrumental in ensuring that all partners know what is occurring day-to-day and that this information can easily be shared to families and community stakeholders. In addition, it allows HRP and OWL to support holistically in all elements of changing systems in school – such as coaching individual teachers as identified by admin staff or finding ways to creatively use space for iPBL needs. More about this is detailed in Additional Information.

Conduct additional training and focus groups of OV staff, families, and students in PBL, SEL, interdisciplinary learning, and other related systems

In May 2024, HRP conducted empathy interviews with young people with ~15 OV 5th grade students, asking questions about the upcoming school year. We asked students about their experience with PBL and what they thought about ideas we had through the Third Coast Learning Collaborative. It was evident that students supported this initiative and wanted additional opportunities to present information in multiple ways (e.g. not just writing, but also drawing, speaking, role playing, etc.)

In Spring, Fall, and Winter 2024, OWL conducted 1:1 empathy interviews with members of the OV teacher and administrative staff. In these discussions, it was evident that many teachers were excited and happy to be part of the project but were concerned about the workload and relative sustainability of the work. This helped our team developed processes and protocols to lessen these potential barriers; as well as offer coaching throughout Fall 2024 on documentation strategies to have more efficient planning meetings.

In addition, Summer 2024 was the “kick-off” week of training for the ‘24-’25 school year. We had 100% attendance from OV teachers, plus full-time attendance from a special education coordinator and pop-in visits from OV administrators and community members. Teachers self-rated their understanding of PBFDA and iPBL at 87.4% and 92% respectively. Prior to these sessions, teachers self-rated their understanding at 64% and 71.1% (a +23.4% and +20.9% increase).

Create and identify advisory board

HRP worked alongside OV and RP to identify an advisory board consisting of OV and RP teachers, family members, community members, and students in Summer 2024, meeting formally starting in Fall 2024 (and continuing in Spring 2025).

Randomly assign students for study

UVA was able to randomly assign students at OV with minimal issues. Only one family desired exclusion from random assignment (being assigned to the BAU control group) and no families were excluded from the study. HRP and UVA helped design print-outs and digital newsletter materials for OV to send home to families detailing the study. There was little communication received back, which we considered a positive given the massive implications and changes we were making in this first year. Students were randomized with weights for IEP status (ensuring equal proportions of students with IEPs were assigned to each teacher) and band/choir sign-ups (ensuring equal proportions of students in the arts were in each cohort for scheduling purposes).

Create educational resources, onboarding tools, and systems for student-centered concepts (such as assessment, curriculum)

Human Restoration Project created four original onboarding documents to iPBL and PBFDA which were utilized in our Summer training, plus utilized many publicly available training documents throughout our sessions. Our new training materials included:

- Assessment Mapping: A tool to help educators draw parallels in a new form of assessment through the lens of ecology and research on self-directed learning & a universal design for learning. Educators draw out how assessment interfaces with learning, teacher reporting, portfolios, and family & caregiver communication.

- Creative Keywords PBL Brainstorming: The first step towards unlocking a world of imaginative project ideas for fostering creative thinking and active participation among students. Meant to help “think different”, this kit is a collaborative brainstorming exercise to reimagine what’s possible in the classroom. Using dice rolls, project brainstormers are defined to creative confines that spurs divergent thinking.

- Finding Our North Star: A collaborative community building activity about connecting our core values, people, places, hobbies, strengths, assets, and more.

- Systems Visualizer: A simple tool for laying out elegant systems design across the various facets of TCLC.

All of these materials are available under an open license on our grant project website: https://www.thirdcoastlearning.org/resources.

In addition, HRP developed protocols to help manage this project:

- A back-end Notion database for tracking meeting notes, financial stipends, hours logging, and more.

- Observation logs for iPBL & PBFDA with integration into our Notion database.

- A standards-organizer matrix which maps ongoing projects to standards across OV 6th grade.

- A Project Planning Organizer to serve as documentation and alignment for iPBL projects within the frameworks and systems we’ve developed.

Conduct coaching, observations, and additional pedagogical training

HRP has conducted bi-weekly (twice monthly) virtual meetings with the OV 6th grade teachers starting at the beginning of the school year in September 2024. These meetings had a 100% attendance rate by teachers and consist of co-planning projects, clarifying stipulations of the grant, and coaching best practices in implementation. In addition, HRP and OWL have conducted impromptu 1:1 meetings on an as needed basis with educators seeking additional support and clarification.

Both HRP and OWL have also done similar in-person training and reflection meetings in Fall and Winter 2024, with HRP focusing on needs of the project and additional supports (e.g. a SWOT analysis) and OWL focusing on empathy interviews and reception to the grant.

Develop website for sharing student and educator success in program

HRP created the Third Coast Learning Collaborative website in Spring 2024 and has consistently updated this page with progress on the project, free resources, and videos of student projects and reflections.

In addition, HRP began a monthly TCLC newsletter in March 2024 for internal use (e.g. teachers, administrators, HRP, OWL) with updates on the project and necessary communication.

Begin advisory board meetings

In our Fall meeting, we provided a project overview, gave time for students in attendance to share their experiences, provided time for families to reflect alongside them, and invited interested RP teachers to listen and learn for their upcoming first year in 2025-2026.

The highlight of this event was a young person sharing their positive experience with TCLC – a student who rarely wanted to come to school and had attendance issues in 5th grade who now can’t wait to attend and fully engages with their learning. Their mom additionally shared how moved she is by this work, especially considering their child’s learning disabilities having impacted previous year’s ability to fully participate in learning.

Recruit students and obtain consent for study

As indicated above, all families consented to the study and one family opted their child out of the TCLC cohort.

Conduct trainings and observations at Reeths-Puffer in preparation for 25-26 school year

HRP began recruitment efforts for the upcoming school year (2025-2026) with RP in Fall 2024, having RP teachers attend our first advisory board meeting and meeting with educators at RP Intermediate School during our in-person visits. Teachers at RP Intermediate School began prototyping a “year 0” this school year based on suggestions made by the OV 6th Grade team. They have not changed their schedule, but are experimenting with project-based learning. They have identified all 4 members of their first year team. HRP started its first formal training of RP educators in early 2025.

Conduct trainings and observations at Orchard View in preparation for 25-26 school year - 7th grade

All the same holds true for the OV 7th grade team, with the only difference being that we are still missing one volunteer teacher sign-up for the 7th grade cohort. We anticipate that this will be remedied in early 2025 as we identify the best fit.

All of the above aligns with our project goals. Teachers exceeded our goals in self-reported understanding of the training in Summer 2024 and had 100% attendance in all of our trainings and meetings. In terms of measurable implementation, we fell short of meeting this goal as we worked to help teachers implement more student-driven (rather than teacher-driven) design thinking methodologies with students. That said, this data is based on only the first half of the school year and we see observation scores increasing from the Fall into Winter (and as of writing, much higher in Spring 2025). We anticipate that these measures will rise quarter to quarter and year to year as we continue training, coaching, and feedback.

Disruptions & Challenges

We remain on track with all of the above timeline and as mentioned, are meeting all of our goals beyond working to improve observation data throughout the school year in implementation of TCLC systems.

The only major challenge in our implementation thus far has been working through scheduling the necessary requirements of the grant (e.g. 3 hours of iPBL) within a public middle school schedule with high student:teacher class ratios, making it difficult to move students around. This is exacerbated by difficult to move around arts programs, such as band and choir, that rely on the same teacher across multiple buildings (and therefore have little room for rescheduling). Likewise, the TCLC cohort’s new schedule causes disruptions to previous scheduling and room assignments for BAU (business as usual) and non-related grade teachers, which has led to some pushback. This work is easier at RPI where electives and the arts are all held in the middle of the day, with the same class structure for all teachers.

This will also lead to additional logistical issues in the following years, as we would prefer to preserve common planning for teachers in the TCLC cohort – something not currently in place for the 7th and 8th grade at OV or RPMS. This will require frequent meetings with the OV team to build a schedule that meets everyone’s needs. Importantly, OV wants to implement these systems regardless (easier scheduling, common planning, support for interdisciplinary learning) but is struggling to find a way to do so.

Further, because all Michigan public schools are schools of choice, we do not have reliable predictability in enrollment numbers year-to-year. Although all schools will see fluctuation, OV’s enrollment could change by 10-20% year-to-year, and these enrollment numbers could change staffing and class arrangements. As class enrollment currently appears low for next school year (‘25-’26), we may need to rearrange the entire schedule to accommodate the needs of TCLC. No administrators or district leaders have indicated that this would impact their involvement in the project, but that this will lead to additional logistical hurdles.

Independent Evaluation

The independent evaluation in Year 1 proceeded according to the original design and on schedule. Specifically, Year 1 of the evaluation focused on meeting regularly with the study team, obtaining human subjects approval, partnering with the study schools to develop and pilot study procedures, piloting measures for the impact evaluation, developing strategies for the implementation evaluation, drafting and submitting the partial plan, and making improvements to the project informed by what was learned (see Table B for an overview). This section describes the activities during the reporting period as they relate to the development and piloting primary components of the impact and implementation evaluations, followed by lessons learned and changes made to improve the study.

Table B: Timeline of Evaluation Tasks

Institutional Review Board Approval

In Spring 2024, the University of Virginia’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the project. The IRB determined that they would waive the requirement of collecting written or verbal assent because the evaluation team does not interact directly with students and no identifiable information is shared with the evaluation team. On student and teacher surveys and administrative data, students are identified with their School ID number, and the evaluation team replaces the School ID with a Study ID in files used for analysis. Furthermore, since the relationship between the schools and HRP pre-dated the research, and since the school leaders requested research support for their program, the IRB approved a parental information process in lieu of parental informed consent. Teachers provide written informed consent prior to participating, and consent was obtained from all pilot teachers in Summer 2024.

Impact Evaluation

Parent communication. After obtaining IRB approval, the evaluation team collaborated with the pilot school (Orchard View Middle School) to distribute informational flyers about (a) the TCLC program and (b) the evaluation were distributed to families in Summer 2024. Families were instructed to contact the school principal with questions about the TCLC program, and to contact Dr. Hofkens with questions about the evaluation. Parents could also request to not have their student participate. No parents reached out to ask questions or to request to have their student participate in the program or data collection before randomization.

Randomization. The evaluation team developed a randomization process that ensured timely assignment to condition, with a ⅔ probability of being assigned to the TCLC group and a ⅓ probability of being randomized to business as usual, and a balanced distribution of special education students in each group. In addition, the school requested that (1) students who participate in a program for students with autism be excluded from randomization as they do not participate in general education classes, (2) students who receive intensive behavioral supports be assigned to PBL for scheduling reasons, and (3) the TCLC and BAU groups be balanced in terms of the proportion of IEP students and students who are enrolled in band classes.

In order to accommodate Michigan’s school choice policy and practices (in which parents can wait until August to decide where they will enroll their student), the evaluation team and pilot school decided to randomize students who were in the school roster at the end of the first week of August 2024. On August 9th, 134 students were randomized: 91 to the TCLC program and 43 into business as usual. One student was excluded from randomization because they participated in the autism program. Four students were excluded from randomization and assigned to TCLC because they received intensive behavioral support.

In order to randomize students who enrolled after August 9th, the statistician created a pre-populated set of assignments based on all randomization factors. When students enrolled in the school, the school counselor filled out a Qualtrics form that indicated if the student: (a) participated in the autism program (excluded from randomization), (b) was assigned to MICI supports (excluded from randomization, assigned to TCLC), (c) had an IEP, and/or (d) enrolled in band. If neither a nor b were true, then the project coordinator selected the next available randomization slot that was consistent with c and d. Generally assignment by the project manager occurred within one hour of receiving the information provided by the school. Overall, 21 students were randomized through this procedure on a rolling basis through November 2024 (12 TCLC, 9 BAU).

Student Surveys. Student surveys were designed in Qualtrics and included 62 items from scales and subscales outlined in the grant proposal - including measures for student engagement in learning, well-being (hope, happiness, optimism, emotional and behavioral problems), belonging and feelings about school. Surveys included random “fun fact” breaks and the evaluation team provided headphones to give students the option of using a text-to-voice program on their computers to have the items read to them.

In Fall 2024, the evaluation team traveled to the pilot school to facilitate the web-based Qualtrics surveys with students. Before administering surveys, students were given information about the study and surveys, informed about confidentiality and voluntariness of participation, and encouraged to provide their true and honest answers and to ask questions if they did not understand. Students in the BAU group completed surveys during a class period in a group of ~25 students; whereas students in the TCLC group took the survey in their interdisciplinary PBL blocks, which consisted of a combined group of 50 students. Students asked questions about items throughout survey administration. On average, it took students approximately 20 minutes to complete the surveys (19 BAU, 21 PBL).

Teacher Surveys. Teacher surveys included 11 demographic questions about the teacher and 20 items that they completed about students assigned to their homeroom. Items were from scales submitted in the grant about the quality of their relationships and the behavioral problems and agentic engagement of each student in their class (teacher-reported outcomes outlined in the grant). On average, it took teachers 60 minutes to complete each survey. Five out of six teachers completed the survey. However, there was significant missing data for the behavioral problems and conflict with student scales (see what was changed as a result in the following section).

Implementation Evaluation

The primary focus for the implementation evaluation during the reporting period was to define and test fidelity of implementation indicators and thresholds that would be used throughout the project. In Summer 2024, the evaluation team traveled to Muskegon, MI to attend the Summer Design Institute. The team noted key components of the program and completed attendance and satisfaction forms for the event. Completion rates for these forms was 100%. The evaluation team also initiated a process of tracking and operationalizing key components, which are outlined in the project’s logic model, and started to draft (1) fidelity metrics and thresholds, and (2) strategies for documenting direct components.

Figure 1. TCLC Logic Model

Evaluation Lessons Learned and Improvements Made

There were no disruptions or delays in the pilot activities that took place during this reporting period. The evaluation team did, however, make the following improvements.

Parent communication and randomization. Based on feedback from both participating schools, we made the decision to shift the timing of parent notification and randomization from summer to spring. This will give parents more time and opportunities to learn about the program and ask about the research, will give more time for the schools to develop their class assignments and school schedule, and will ensure that all staff are available to provide the information needed for randomization.

The schools also developed additional strategies for parent communication, including an informational video filmed by the school principal explaining the program and evaluation to accompany information sent to parents about the project.

Student surveys. The evaluation team made four changes to the student surveys based on what was learned from the Fall 2024 survey implementation. First, the optimism scale was dropped because of the number of students who asked what optimism means during survey facilitation. Given that there were other scales to measure multiple indicators of well-being (including happiness, hope, and emotional problems), the team determined that dropping the optimism scale would produce a survey that was shorter and easier for students to understand overall.

Second, the team decided to create their own audio files to accompany each item for the full project. Several students reported that the text-to-audio program on their computer was difficult to use. The evaluation team has expertise in developing audio to embed in the survey.

Third, the evaluation team decided that students in both groups should take the study surveys in the context of a single classroom consisting of 25 or fewer students. While reliability for all scales met WWC criteria for inclusion (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.60), internal consistency among data received by BAU students was slightly higher on many of the scales than data received by TCLC students. The evaluation team determined that differences in the survey implementation could have contributed to this difference. TCLC students completed the survey in their PBL block, which included two groups of students in a large room that can include up to 50 students. In contrast, BAU students completed the survey in a regular classroom with 25 or fewer students. The TCLC classroom had more movement and sound during survey facilitation and the evaluation team determined that the number of students likely contributed to the difference.

Finally, the team determined that they would develop a strategy for students who were absent to take the survey to reduce the overall attrition due to missing data.

Teacher surveys. The evaluation team made significant changes to the teacher survey based on what was learned in Fall 2024. First, when processing the data, the team noticed that there was a significant amount of missing data (due to non-response) for some of the items about behavioral problems and conflict with students. Since the project will receive information about student behavior through disciplinary referrals, which are also administered by teachers, the teacher report of student behavioral problems was dropped. Also, given that students provide information about their relationships with their teachers in the scales about belongingness and feelings about school, the team decided it was also not necessary to collect these items. Also, one teacher opted to not complete any surveys. Given the relatively small number of teachers, the team determined that it would be better for the study to not rely on teacher reports for student outcomes and instead use the teacher survey to learn more about teaching practice and program implementation.

Sustainability and Scaling

Impact Beyond Partners & Implementation Sites

We are pleased to report that our project has already started making an impact beyond our implementation site.

First, we have seen an impact on both RP and OV’s implementation of iPBL and PDFBA beyond the grade levels we are targeting. RP High School has several teachers beginning a portfolio-based process modeled after the work of TCLC, using resources from our summer training as a branching-off point. This is modeled after their Portrait of a Learner and plans to scale across all levels of the high school. This is exciting for us, since it implies a continuation of innovative practices from 6th through 12th grade, showing that scaling a model of this project vertically is not only possible, but sustainable even without our organization’s direct involvement. Similarly, we have seen TCLC practices (e.g. PBL) as a learning track that professional learning communities (PLCs) have targeted at OV High School.

At a larger scale, districts within the Muskegon Area ISD, the collective servicing network consisting of RP, OV, and 10 other districts have expressed interest in becoming involved in the TCLC program. At the beginning of the school year, we reached out to in-house documentarian professionals at the ISD who already capture and document learning within the districts to assist us with capturing projects within TCLC. These videos have captured each major event and project in our initial cohort, then shared on the district's YouTube pages, our organization’s social media, and the TCLC webpage. Because of ample social media traction on Facebook and LinkedIn, many surrounding communities (and respectively, their districts) have wanted more information on this project, leading to opportunities to expand if/when a midphase application is available. Given previous communications, we are confident that Muskegon Public Schools (urban) and Montague Schools (rural) would be highly interested in joining in future years.

This continues to be true for surrounding ISDs, namely the Ottawa Area ISD (south of Muskegon) and Kent ISD (southeast of Muskegon, comprising Grand Rapids). Based on the documentation and sharing of information on TCLC, both ISDs arranged meetings with HRP to talk about becoming involved in this project in future years. Both ISDs want to explore opportunities to commit the majority of their districts to this program if/when a midphase grant is available, which would consist of ~30 additional districts from rural, suburban, and urban areas. Similarly, we have had multiple districts across the country reach out to us about this opportunity and express interest, including in Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, and Columbus, OH.

Further, we have had numerous downloads (~500) of TCLC-created resources with multiple inquiries to our website contact page thanking us for using these resources that they have utilized with their school teams.

Meeting Scaling Targets

Our project is currently in its first pilot year and is set to expand up one grade level at OV and into a neighboring district (RP) in 6th grade. We are currently set to expand into both schools as predicted with 100% commitment from OV 7th and RP 6th. Further, we have taken steps to secure teacher teams at the final phase of scaling in the early phase grant: 75% of the team is assembled in RP 7th grade and 50% of the team is assembled in OV 8th grade (Year 3).

It is worth noting that our “pool” of interested teachers in expanding our program is primarily via teachers who intentionally opted out of the TCLC cohort in its first year. Or in other words, the business-as-usual control group who decided they did not want to commit to this programming are now interested in joining after one year. We see this as an important data point since exposure to the TCLC program has improved trust of our work, as opposed to turning people away.

We have not received any indication that families will be less likely to opt into programming in future years, with anecdotal evidence indicating that families are inquiring on how to be involved with the TCLC program.

Both districts (OV & RP) have invested in their business-as-usual teams, exploring similar ideas expressed by TCLC (namely project-based and place-based learning), with an effort to sustain these practices after the 5 years of the grant and capture interest while investment is being made. Funds from our grant are being used to provide project supplies to the business-as-usual group.

Further, scaling up through a potential midphase expansion is starting now, as indicated in Impact Beyond Partners & Implementation Sites.

Open Licensing Requirement

As laid out in our project narrative, TCLC is distributing all grant resources via the Third Coast Learning Collaborative website (https://www.thirdcoastlearning.org). All of these works are available under a Creative Commons attribution, non-commercial, share-alike international license as directed by 2 CFR 3474.20. So far, we have released multiple training resources (see Create educational resources, onboarding tools, and systems for student-centered concepts (such as assessment, curriculum)) as well as project showcases with videos and resources for each major TCLC in-class project.

Additional Information

By far the most important, yet not a formal part of our work this year has been the inclusion of documentation experts from the local school ISD (intermediate school district – a collection of districts in Michigan). The Muskegon Area ISD has two documentarians whose role includes professional filming of projects and field trips happening at local schools. For every project in TCLC so far, we have utilized them to capture learning-in-action. Based on its success, we plan on including documentation in all projects going forward.

These videos have had a large and meaningful impact on our work – allowing videos to be shared by the schools and our organization on social media and via our websites, and has led to positive feedback from across the community. This is how our organization is finding additional interest in our work (see Sustainability and Scaling), and how schools are ensuring that families are informed about what is going on at the building – which has been virtually all positive feedback.

In addition, we have included part of Human Restoration Project’s broader work with schools as part of the TCLC process: empathy interviews. Prior to applying for TCLC, we utilized student empathy interviews (small focus group conversations with young people) to gauge what changes were most needed to reimagine school to meet students' academic, behavioral, and emotional needs. This is how we built our EIR application. Likewise, we are using empathy interviews with incoming cohorts to TCLC (both for incoming students and teachers) to determine the best support in implementation. For example, with young people we “focus test” project ideas for the upcoming school year and see what students think about interdisciplinary project-based learning, which can help us in our onboarding process. Or with teachers, we can determine relative attitudes toward the fundamental notions of our grant so that our training can best suit their needs.

Further, we have found the use of biweekly (twice per month) all-hands meetings to be invaluable for this project – both to keep people involved and to ensure we are consistently aligned with messaging/communication. Every two weeks, we meet with school leaders from both the OV team (currently in implementation), RP team (starting in 2025), the local ISD, OWL, and our evaluation team at RAND. These meetings serve as short updates for each organization to share, plus time to ask any clarifying questions. This serves as an additional branch of communication to emails and a monthly newsletter sent to TCLC organization leaders.

Appendix and Attachments

- School Resources (available on the resources page)

- Student showcases (available on the showcases page)

- Article: School-within-a-school uses PBL to help students make a big move (District Administration, January 4th, 2024)

- Joshua Smith, the principal at Orchard View Middle School, submitted the following application which focuses on the Third Coast Learning Collaborative at OV MS. This application led to OV MS being nominated. Out of over 15,000 school districts in the nation, hundreds of schools were nominated. Three schools were finalists in the main category of “Academic Excellence”, including Orchard View Middle School.

In approximately 150 words, describe the problem of practice that you were trying to solve with this initiative. How did you know you needed to solve this problem?

As middle school students explore their identities and the world around them, they sometimes disconnect from school, contributing to high absenteeism—a significant issue in Western Michigan and at Orchard View Middle School (OVMS). To address this, OVMS launched a "belongingness" initiative, focusing on making every student feel connected to the school. This included implementing SEL curriculum, MTSS structures, and shifting teaching methods. To tackle absenteeism specifically, OVMS created a school-within-a-school that emphasizes engaging students through interdisciplinary, project-based learning and feedback-driven portfolio-based assessment instead of traditional grading. A $4 million, 5 year federal Education Innovation and Research (EIR) grant supports this initiative, providing funds for supplies, field trips, and teacher training. Additionally, this grant supports a formal randomized control trial, studying how our school-within-a-school cohort could impact student well-being, motivation, engagement, and absenteeism.

How did you determine what you were going to do? How was this initiative chosen?

Shifting teaching practices is no easy task, and many educators find it daunting to move away from traditional methods. Convincing teachers to adopt a hands-on, student-centered approach can be especially challenging. Despite the resistance, a few passionate teachers at Orchard View Middle School recognized that a change in how content is delivered was necessary to truly help students feel they belong. These teachers made education more meaningful by focusing on connecting students to their learning and engaging them in ways that revealed hidden interests and talents. Initially, only a small, willing group embraced this shift, but in 2022, the vision expanded into a school-within-a-school model, beginning with sixth graders. As momentum built, more teachers joined, growing from four to nine. While it remains challenging, within three years, over half the staff at OVMS will have transitioned to Project-Based Learning (PBL), demonstrating the power of persistence and innovation.

What actions did you take to start and implement this initiative?

Orchard View Schools launched a “belongingness” initiative to make school meaningful and welcoming for students. Central office collaborated with stakeholders to develop a Portrait of a Graduate featuring five key attributes: resilient citizens, creative critical thinkers, curious collaborators, adaptable communicators, and determined individuals. These attributes were then broken down into grade-band competencies.

In partnership with the non-profit Human Restoration Project (HRP), OVMS conducted representative student focus groups to ensure that student voice and equity were central to instruction and building-level decision-making. Using this data, teacher teams aligned their teaching strategies with the community-generated Portrait of a Graduate.

While many teachers were hesitant to change their teaching methods, a small group began experimenting with project-based learning and design thinking, two things that students readily identified as beneficial to their engagement at school. Teacher success in implementing this pedagogy led to the creation of a formal school-within-a-school model starting in sixth grade. To support this initiative, OVMS and HRP secured a $4 million EIR grant from the US Department of Education, which will fund project supplies, field trips, and teacher training. Over the next three years, this innovative approach is expected to expand to half the school spanning grades 6-8.

Who else was involved in implementing this initiative?

This initiative was driven by teachers from the outset. Once it became evident that interdisciplinary project-based learning (PBL) created the authentic, hands-on environment teachers and students sought, the next challenge was securing supplies and training. To address this, Orchard View Middle School (OVMS) partnered with the Human Restoration Project (HRP), which played a key role in obtaining additional funding and resources. HRP leveraged its existing relationship with Open Way Learning (OWL), a nonprofit organization that supports over 40 districts across the U.S. in transitioning to authentic, hands-on PBL experiences.

Together, HRP and OVMS applied for an EIR grant, alongside University of Virginia (UVA) to oversee the implementation through a randomized control trial, data collection, and within the What Works Clearinghouse framework. This collective effort ensures that OVMS teachers are well-supported as they innovate and enhance student learning through project-based education. A neighboring school was also written into the grant to explore this process (which will follow OVMS one year later, contextualizing the process to the best of their ability). All of these groups have formed what is now the Third Coast Learning Collaborative (TCLC).

How did you monitor the benefits of this initiative?

A survey was developed to directly measure students' sense of "belonging" at school, giving them a voice in assessing their own connection to the learning environment. In addition, Human Restoration Project conducts quarterly check-ins with both students and teachers, gathering valuable focus group data to further inform the initiative. Open Way Learning remains a steadfast partner, providing ongoing support to teachers as they transition to new instructional practices.

The primary metric for evaluating the success of this initiative is absenteeism. The EIR grant specifically aims to achieve a significant reduction in absenteeism among students participating in the project-based learning (PBL) cohort. By closely monitoring these metrics, the program seeks to ensure that the PBL approach not only enhances student engagement but also fosters a stronger sense of belonging, ultimately leading to better attendance and overall student success.

Upload relevant evidence or artifacts that amplify your entry above.

https://www.thirdcoastlearning.org

What were the results of this initiative?

Almost immediately, students reported feeling a stronger connection to school. In focus groups, they shared both the challenges and successes they encountered in their PBL classes. Remarkably, even before the intervention of funding and additional project support, the prototype year saw discipline referrals from the sixth-grade cohort as significantly lower compared to their seventh and eighth-grade peers. Survey results confirmed that these students felt a heightened sense of belonging at school.

Walking down the sixth-grade hallway, it's evident that something special is happening. Students are visibly excited and deeply engaged in their learning. They’re not confined to classrooms—they're in hallways, STEM labs, or out on field trips, actively exploring and applying their knowledge. The most powerful indicator of success is the smiles on their faces as they discover a sense of purpose and see its connection to their school experience. This initiative has truly transformed the student experience, fostering an environment where learning is both meaningful and joyful.

What advice would you offer to a district that wanted to replicate this initiative?

To replicate a successful program, begin by establishing a clear vision and engaging all stakeholders to ensure alignment. Recognize that shifting teaching practices can be challenging, so start with a small group of enthusiastic teachers to pilot new methods like project-based learning (PBL). Actively gather and incorporate student feedback through surveys and focus groups to ensure the program meets their needs and fosters a sense of belonging. Partner with external organizations for funding and expertise, such as Human Restoration Project and Open Way Learning, to provide essential resources and training. Monitor key metrics like absenteeism and discipline referrals to assess the program’s impact and make necessary adjustments. Celebrate successes to build momentum and share positive outcomes with the community. Be patient and persistent, allowing the program to expand gradually as more teachers and students experience its benefits. Secure funding early to cover costs and sustain growth.